The University Farm, Past and Present: A Timeline

by Claire Dutkewych, Matthew Marner, and David Duke[1]

Edited by Jodie Noiles

The Birth of the Acadia University Farm

The Acadia University farm boasts a history as rich and complex as the university itself. The farm was established in one sense almost inevitably, as a reflection of the agricultural element of Acadia’s history, and also in a practical sense as a means of supplying the school with food resources to sustain the students that boarded on campus as they pursued their studies. In its initial incarnation the farm was almost as old as the institution itself.

Photo Credit: First College Hall. 1860. Photograph Collection. Esther Clark Wright Archives, Acadia University

The idea of a university farm grew from the rich agricultural heritage of the Annapolis Valley. In particular, the Annapolis Valley apple industry was a hallmark of the young nation’s agriculture in the second half of the 19th century, and new technologies and practices developed by the industry spread across the British Empire. For almost a century Great Britain and Western Europe were the main markets for Nova Scotia apples, and market demand drove technological innovation in the Valley. It was felt that a “scientific” – that is, experimental – farm, located on the Acadia University campus, would be a useful incubator for new practices and technologies and so, at the annual meeting of the Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association, held in Wolfville in 1893, Chip Parker called for an experimental fruit farm and horticultural school to be established on the Acadia University campus. Parker was concerned that the government had established five other experimental fruit farms in the Maritime Provinces, yet none were sited in the Annapolis Valley, which was the pinnacle of Nova Scotia fruit growing at the time.[2] At the meeting in Wolfville, Parker famously said “We’ve got the men, we’ve got the money, all that is needed is to put them together.”[3] Parker helped to create a committee that lobbied governments in both Halifax and Ottawa and which led to the creation of the Wolfville School of Horticulture at Acadia in 1893 and the Dominion Experimental Farm in Kentville in 1910.[4]

The Horticultural School employed Acadia University classroom space and was fully supported by the provincial government. The students were provided with free tuition, and the school’s first sixty students were enrolled in 1893.[5] The following year, the school’s infrastructure expanded with the addition of a large greenhouse and classroom, as well as a laboratory. This helped to increase the school’s capacity and popularity. As the school became more popular, it outgrew the extra space that the university was able to offer, and eventually relocated to its present location in Truro, Nova Scotia in 1905.[6] The impact of the school on campus, and its relocation, generated considerable interest in maintaining horticultural activities at Acadia, as there was a reluctance to abandon the activities that the school had brought to the university.

1895-1920

Parallel to, but not connected with, the creation of the Wolfville School of Horticulture, other farming activities had been ongoing at Acadia. From the time of its establishment as a college, Acadia had been in possession of significant tracts of farmland, which had been worked for the benefit of the university. In 1895, Dr. Atwood Cohoon moved to formalize this activity, advocating that the farmland, which included a small herd of seven cattle and fiteen pigs, [7] should be integrated into the university’s life as a supplier of fresh milk and produce to the dining hall.[8] He also envisioned that the campus farm would also provide students with an opportunity to save money on tuition and board through their physical labour.[9] Dr. Cohoon became superintendent of the farm and employed Billy Oliver as the head labourer, giving Oliver the responsibility of all livestock husbandry.

Right from its inception the farm enjoyed great success by engaging both the students and faculty in the task of developing new techniques and ideas to supply more resources for the campus dining hall. In an article from the Acadia Athenaeum in 1900, the author describes the impact of the farm on campus life, portraying it as a“large farm near the willow tree in the rear of the college, [with] the cattle and horses passing back and forth, and the implements of farming lying around.”[10] The farm continued to succeed financially as well, generating a revenue stream independent of its supplies of produce to the university. The year 1912 saw the farm’s annual net surplus at $578.11, equivalent to $12,341.26 in 2015 dollars.[11], [12] However, the farm’s barn started to show signs of age, and in January 1913 a post in the Acadia Bulletin revealed plans to build a new barn just south of College Hall.[13] This new barn would be much larger and would be capable of accommodating twenty cattle, which would be enough to supply the all boarding residences with fresh milk.[14] The barn cost the university $1,000 and was paid for by the sale of the Masters property at St. John–a legacy gifted to the institution.[15]

Amidst all of this success, the farm did not always run smoothly; as was the case in 1911, when Wolfville’s medical officer, Dr. George E. DeWitt, reported to town council that there had been an epidemic of typhoid fever in March and April of 1910 that had directly affected the women of Seminary House.[16] Dr. DeWitt suspected the cause of the infection was that the water used to wash the milk cans before transport to dining hall had been drawn from a contaminated well.[17] This is perhaps why the school was so eager to upgrade the farm facilities in the next few years. The upgrades, undertaken in 1914, were considerable: the farm’s pasture was improved by a thorough cleaning and seeding, new pipes were laid for the supply of water from the reservoir to the barn, four stanchions were added for cows and a root cellar was excavated.[18] The new water-supply and irrigation system cost the school $5,360.49,[19] more than the barn itself, but was essential following the outbreak of typhoid fever. The new barn was completed in 1913 and was also a major improvement on the previous model, as it possessed a cement foundation, the an attached cement piggery and root cellar, and an adjoining farm cottage in which the farm help could reside.[20] The new farm also offered enough room to house twenty cattle and supply enough additional space for hay and farm machinery storage.[21] By 1914, the farm was operating at a surplus of $605.32, monies generated in addition to the task of supplying the boarding residences with produce and dairy.[22] In fact, the farm produced an abundant crop of potatoes that year– yielding about 800 bushels, approximately 40,000 lbs., of produce.[23] This was a rather remarkable feat and reflected the success of the farm and its importance to the school. The farm continued to use its financial security as a base to expand the facility in order to meet the demanding nourishment requirements of the growing enrolment at the university. In May 1917, the school purchased thirty-nine acres of orchard land that had become available near the barn for a low price of $1,500, with the intent of expanding its fruit orchards.[24] This became a vital element of the farm as the fruit from the orchards supplied the dining halls and was able to be preserved for use in the winter months, when produce was scarcer.[25]

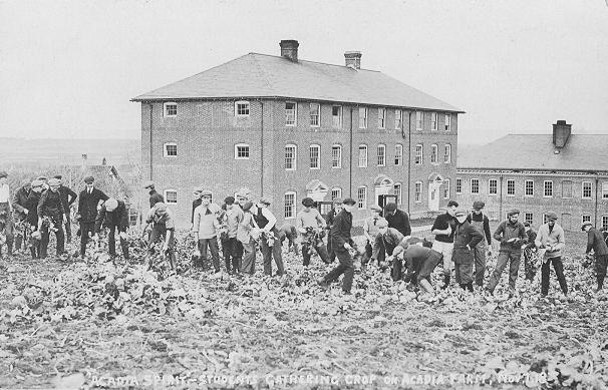

Photo Credit: Harvesting Turnips. 1918. Acadia Photograph Collection 784. Esther Clark Wright Archives, Acadia University.

The First World War created a demand for labour on the farm as most able-bodied men had volunteered to go overseas. In November 1918 the university formally requested student assistance for the fall harvest, due to a shortfall in labour, and in return the students would be excused from classes.[26] A picture in the January 1919 Athenaeum displays the students gathering in the fields [near] present day Willett House to harvest the crops for the year and in one day they managed to harvest the entire crop of turnips, which consisted of about 800 bushels in total.[27] This was a valiant display of effort and school spirit, in which the students had become invested in helping the school with its harvest. The Acadia farm had by this point therefore become more than just a source of nutrition and school capital – it had become a defining characteristic of the university and a representation of the rich bounties offered by the Annapolis Valley. There are many examples that demonstrate the centrality of the farm to campus life: Donald Oliver refers to the gangs of students who would turn out to the fields harvesting crops, and then switch to the orchards to pick fruit for the next winter’s pies.[28] Even the barn itself was the preferred student “hang out” spot, and Oliver recounted the echoes for which the old barn was famous, with students commonly marching up to the barn to have fun with the echo effects in order to relieve stress from the hectic exam times.[29]

1920’s

By the 1920s the farm’s profitability had begun to slip to the point where it had come to represent a financial liability to the university. The costs of the updates to the farm’s facilities in the mid 1910’s were still an encumbrance and the mechanization of the agricultural economy made food more affordable; a self-sustaining university farm became less important. In the 1925 treasurer’s reports from the Acadia Bulletin show that the farm was operating at an annual deficit of $993.28.[30] This deficit is approximately $14,075.75 in 2015 dollars[31] and it was simply not a feasible long-term burden for a school that had a limited source of income drawn from small enrollments. The deficit had grown annually in the 1920s, from $697.23 in 1922, to $993.28 in 1925. The last report of the farm’s income was included in the June 1928 Acadia Bulletin, and showed an annual deficit of $1,505.04, as well as an accumulated deficit of $9,605.48. This was a very large amount for the time and called for a dramatic change in policy.[32] Rather than continue to sacrifice large amounts of income for the purpose of providing dining halls with food and dig a larger financial hole, it was decided to rent the farm facilities out in order to provide the university with a consistent income. Accordingly in the late 1920s the farm was leased to local farmer Walter Duncanson.[33] Under the terms of the lease, which expired in 1956, Duncanson continued to supply the unversity with produce and dairy, but could farm the property at a profit to himself.[34] The farm’s rental income is first reported in the university treasurer’s accounts in 1931, to the sum of $471.81, or approximately $7,213.58 in 2015 dollars.[35], [36] Under Duncanson’s stewardship the farm’s financial situation stabilized but it was no longer as essential to the institution as it had once been.

1930s and 1940s

Photo Credit: Nova Scotia Archives. Nova Scotia from the Air: The Richard McCully Aerial Photograph Collection, 1931. No. 9, Negative no. 353.

The changing relationship between farm and university is perhaps reflected in the noticeable lack of information in university documents in the 1930s and 1940s regarding the farm. One event that was recorded in the June 1934 edition of the Acadia Bulletin, was the passing of William Oliver, who had come to be known informally on campus as “the boss” on the farm. This was reported as marking the end of an era on the Acadia campus.[37] One source of consistent information concerning the farm in this time period was the accounts of the university treasurer which reported rental income annually. The tale those reports tell is an uneven one. The amount of rent the school received declined as the 1930s progressed, falling to only $263.61 by 1939.[38],[39] This diminishing rental income indicates that the farm had not been as productive as it once was and seems to fit in with larger economic hardships generated by the Great Depression and the general decline in the Annapolis Valley fruit industry. In 1931, Professor J. Coke, the Assistant Commissioner of the Department of Agriculture Economics, surveyed the farms in the Annapolis Valley from Falmouth to Paradise and determined the value of the properties with crops and farming equipment against the cost of the real estate alone.[40] The results, published in the April 30th 1931 edition of the Wolfville Acadian, made for sober reading: Coke calculated that the average value of real estate – including crops, stock and farm machinery, and equipment was $16,166.00. This was compared to the value for real estate in the form of land and buildings alone, which was $12,890.00. This only includes a land improvement value increase – that is, the value added by farming – of only $3,276.00.[41] This survey displayed to the public the harsh reality that farming did not enhance the value of the land, because of the expansion in the U.S and Europe of fruit farming activities and the difficulty encountered by Valley farmers in improving their crop yields. Worse was to come: the economic destruction inflicted by the Second World War on Europe, together with the long period of economic instability that followed it, robbed the Annapolis Valley fruit growers of one of their prime markets, which caused severe problems for the industry. Increased competition from domestic production in Europe and growing capacity in the U.S.A. also drove apple and fruit prices down, making exports from Nova Scotia uncompetitive in the already-shrunken European market and in the growing but heavily-supplied market south of the border.

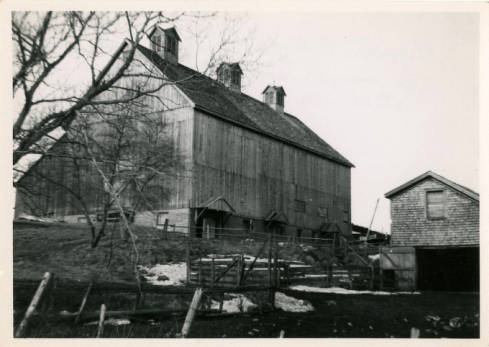

Acadia Farm Barn 1940s. Sherman and Nancy Bleakney Fonds Collection, Esther Clark Wright Archives, Acadia University

Several years of bad crop yields also contributed to the Valley fruit industry’s woes. In 1945, it was noted that perhaps the apple trees in the Valley had become less productive due to their age and height. Thus, Valley fruit growers began a costly and risky transition to new varieties of hybrid and dwarf apple trees that promised greater efficiency and high fruit yields. In the late 1940s the industry continued to decline however, so much so that James Gardiner, the Federal Minister of Agriculture, authorized $1,443,808 in relief to Valley growers for the loss of their 1948 crop.[42] Gardiner continued to bail out the industry in the two years following, supplying another $500,000 and $300,000 to their relief and helping them in the transition process.[43] It is very likely that, even with the guaranteed contract to supply dining hall, the Acadia farm under Duncanson’s stewardship would have experienced hardships similar to those of the larger industry.

1950’s

Although the farm continued in operation into the 1950s, it no longer served as a major source of income or produce for the university, and as the decade progressed the farm was beset by a series of mounting problems, some of which were particular to the farm and some of which were characteristic of the Valley farming industry more generally. This latter factor is readily apparent in the meeting notes from the Nova Scotia Fruit Growers Association (NSFGA), based in Kentville, that recorded a series of bad harvests in the early 1950s. The meeting minutes of 1955 note that the apple harvest of 1953 was at a record low, and hopes for recovery in 1954 were dashed by the devastation inflicted by Hurricane Edna.[44] In 1953, the NSFGA sent delegates to Europe to try and reopen markets lost in the 1940s and were moderately successful in doing so.[45] This, in combination with the expected strong harvest from the new tree varieties, led many farmers to a sense of optimism for 1954. But a series of natural factors conspired to wreck such hopes for success. They struggled with a series of spring frosts that made the pollination process difficult and orchards were then hit by a significant outbreak of the European Apple Sucker, a fly larva that damaged young leaves and blossoms, dramatically reducing potential yields.[46] Although the Sucker infestation hit large commercial operations particularly hard, its effects were felt in orchards across the Valley, including that of the Acadia farm. By this time accounting records demonstrate that Walter Duncanson was struggling to turn a profit and the damage to the apple crop – traditionally one of the most profitable parts of the farm operation – was particularly worrisome.

Despite the rough start to the 1954 season, a warm and well-watered summer allowed the orchards to rally somewhat and farmers looked forward to exporting a good crop to the newly-reopened European markets; the NSFGA reported that more than a decade’s worth of decline was on the point of being reversed.[47] At this point, however, disaster struck in the form of Hurricane Edna, which bore down on the province on September 11, 1954. This massive storm – one of the largest in the history of Eastern Canada – destroyed about 80 percent of the apple crop in the Valley and ruined the trade lines that had been reopened with the U.K., as the Nova Scotia farmers were unable to fulfill the shipment orders.[48] The federal government once again had to help the Valley apple industry by purchasing the wind-damaged crops to use for apple chips, at which they purchased for two cents a pound.[49] Edna’s impact on the apple industry was massive and nearly terminal, as the storm damaged most of the newly-planted trees. Farmers thus faced the challenge of a significant replantation effort, with the associated capital costs, while still dealing with the losses to a tree-line that had never had the chance to bear fruit fully.

The Acadia farm was also ravaged by Edna, which left the barn in shambles and destroyed much of the orchard.[50] Walter Duncanson’s lease to the farm expired in 1956 and, facing considerable capital expense to rebuild the farm and its orchard, he chose not to renew his lease commitment.[51] The university was now faced with a choice: inject significant resources into the farm, to repair the heavily-damaged barn[52] or tear it down and replace it with new construction, and to replace the damaged orchard, or to close the operation down completely. A report by Acadia economist Dr. N. H. Morse, delivered to the 1955 meeting of the NSFGA provides insight into the prevailing opinion on the future of agriculture in the Valley, and hints at campus opinion concerning the future viability of the Acadia farm.[53] Morse’s doctoral research completed at the University of Toronto in 1952 had focussed on the Annapolis Valley apple industry and he can rightly be seen as an expert in the economy and structure of the Valley at this time. His report to the NSFGA, entitled The Economic Position of Nova Scotia and of The Annapolis Valley stated that apples were no longer a viable cornerstone of the agricultural sector for the province, and that a dramatic shift in crop focus would be needed, away from apples and toward a more mixed agriculture incorporating a variety of crops. Such diversification, Morse suggested, would reduce the province’s dependence on agricultural imports from the rest of Canada, and increase the agricultural sector’s economic resilience by reducing its heavy reliance on one crop, the apple. [54] He also argued that attempts to re-establish the British and European markets were likely to be unsuccessful and that the marketing focus of Valley farmers should shift to the United States and the rest of Canada.[55] Morse’s thoughts were likely discussed with Acadia University’s Board of Governors, of which he was a member, because the following year, (when Walter Duncanson’s lease expired), the university determined that the farm was no longer financially viable and opted for its closure, as the land itself had become more valuable to the university than the farming operations undertaken on it. Enrollments had increased and the university was looking to expand its physical structure to accommodate the new students. Farming operations ceased in 1956 and, as Donald Oliver (the grandson of Billy Oliver, Atwood Cohoon’s former “farm boss”) reported in 1960, the barn, “the last significant remnant of the ‘Old College Farm’ has been erased from its position of importance.”[56] The demolition of the barn and the end of farming operations freed up land on which the university then sited four residences – Dennis House, Chase Court, Cutten House and Crowell Tower – as well as a new dining hall, Wheelock, and the university’s new Physical Plant.

The old Acadia farm is a story of local pride that followed the rise and fall of the Valley fruit industry and ultimately fell victim to shifting economic forces. As economies changed, land became more valuable as a site for development as opposed to a foundation of agricultural activity. The physical expansion of the university at the expense of agricultural land in the 1960s and after demonstrates this but it is reflective of larger processes of urbanization and loss of agricultural land in the Annapolis Valley to suburban development. These processes are controversial and still divide communities today.

Although the old University Farm is gone, its importance to the institution remains in the memories of those Acadia graduates and staff who worked on it or who were fed by it. Its reach continues to extend beyond the campus too: Lawrence Welton, a long-time resident of Wolfville and former member of the Wolfville fire department, was touched by the farm and shared a rather funny story about a call he got while working at the fire department in the early 1950s. He recounted that the emergency call was from the Acadia campus concerning a group of pigs that had been “liberated” from the Acadia farm pen and set free in Whitman Hall. The pigs had been greased up by the students as a graduation prank and he recalled that it took the fire department over two hours to recover the animals, which were impossible to catch in their slippery state. Mr. Welton still laughed at the story at the age of 76, as he remembered the Acadia farm as if it was yesterday and it does appear that everyone in the area has their own special memory of the farm. Not only was the Acadia farm essential to life on campus, but it also touched the people of Wolfville.

New Farm

Today the Acadia farm lives a new chapter that promotes sustainability and community involvement, while still focusing on supplying Wheelock dining hall with local and sustainable food options. The new Acadia Community Farm was started in 2008 by two students, Alex Redfield and Hilary Barter and with help from other students, faculty and staff the new farm was born.

Founding Farmers. Acadia Community Farm 2008

In its new incarnation, now under the oversight of Sustainability Coordinator Jodie Noiles, the farm shares some of the same elements of the old Acadia Farm, while shifting focus to a more community-oriented basis. The new farm is located on the dykeland just below the Acadia Athletic Centre at the north end of the university’s campus, and it is common to see people working hard together on the garden plots. The farm is open to both the public and students who are able to receive a plot of land that they can cultivate for their own purposes; as of 2015 approximately 25 community plots were under cultivation at the farm, together with a roughly equal number of plots devoted to university purposes. All members who work plots on the farm ordinarily volunteer their time and labour to maintain the school plots. The school plots represent about half of the approximate fifty plots available, and these plots are cultivated for the purpose of supplying Wheelock dining hall with local sustainable produce, as well as supplying the local food bank as a way of giving back to the community. In 2015 one plot was being used for research into sustainable agriculture, which heralds new potential synergies between the farm and the university community.

The farm in its current incarnation is remarkable for the connections that it forges between elements of the university community and the larger community in which the university is embedded. It is not uncommon to see students, retirees, educators, and volunteers working together and alongside one another, sharing knowledge, techniques and ideas to grow bountiful harvests and increase cultivational skill.

The farm is also being integrated into campus activities in other ways. Sustainable food classes have been added to the curriculum, which as part of their activities focus on seeding and raising seedlings in the KC Irving Centre greenhouse to be planted on the farm in the spring. A Farm Coordinator is appointed from the student body each year and is responsible for working with the Sustainability Coordinator and the community to develop a plan for the year and promote sustainability, while ensuring that everyone is connected and informed on the ongoing activities on the farm. The Farm Coordinator tracks the progress of the season and maintains a blog and website for the information of the larger community. The farm follows organic practices and the use of pesticides or GMOs is not permitted, as it is a facility philosophically geared towards environmental sustainability. The farm has been a great success as a supplier of fresh produce in the Fall Term to Wheelock Dining Hall, and since 2009 it has been a regular contributor of fresh produce to the Wolfville Food Bank as well. The farm also allows students living in apartments or residences to cultivate their own garden that they otherwise would not have access to. It is definitely a remarkable story and represents collaboration between the university, the community, the faculty, and even elementary and high school students are becoming involved. Participation numbers are growing yearly, and in the twenty-first century the farm continues to build upon legacy of the first incarnation of the farm that closed more than half a century ago. The new farm’s success is perhaps indicative of the desire of community members, from young to old, both on campus and off, to rediscover our connection to the land and, through that, our connections to each other.

Bibliography

1. Primary Sources

“Billy, As We Have Seen Him.” Acadia Athenaeum, May 1915, p. 407-411

“Death of Mr. William Oliver.” Acadia Bulletin, June 1934, 21

“Income of the University” Acadia Bulletin. 1931.

“Income of the University” Acadia Bulletin. 1935.

“Income of the University” Acadia Bulletin. May 31, 1939.

“Income of the University” Acadia Bulletin. May 31, 1940.

“Mr. Oliver’s Illness”. Acadia Bulletin. January 1922.

“New Barn”. Acadia Bulletin. January 1913, p. 4-5.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. November 1912.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. November 1913.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. November 1914.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. November 1915.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. November 1916.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. November 1917.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. 1918.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. 1922.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. July 31, 1925.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. July 31, 1926.

“Treasurer Accounts: Farm” Acadia Bulletin. 1929.

Morse, N.H. “The Economic Position of Nova Scotia and of The Annapolis Valley”

Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association: Annual Report. (1955): 90-95.

Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report 1954.

Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report 1955.

Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report 1956.

Oliver, Donald. “Farm, Former Part of College Domain Erased From Scene” Acadia Bulletin, September 1959, p. 33-35.

Sutherland, Dawn. Interview with Lawrence A. Welton, May 25, 2015.

“Valley Farms Are Analyzed” Wolfville Acadian, April 30 1931.

“William Oliver” Acadia Athenaeum. June 1911, p. 265.

2. Secondary Sources

Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator

http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/

Dutkewych, Claire. “The Acadia University Farm.” Unpublished Manuscript, 2014.

Hutton, Anne. Valley Gold: The Story of Nova Scotia’s Apple Industry. Petheric Press Limited, 1981.

Sheppard, Tom. Acadia University. Images of our Past Series. Halifax, Nimbus Publishing. 2013.

________. Historic Wolfville, Grand Pré and Countryside. Images of our Past Series. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2003.

[1] Claire Dutkewych graduated B.A. (Hons) History, 2015; Matt Marner graduated B.A. ESST, 2015; David Duke is Coordinator of the Environmental and Sustainability Studies Program and Associate Professor in the Dept. of History and Classics, Acadia University.

[2] Anne Hutton, Valley Gold: The Story of Nova Scotia’s Apple Industry. (Halifax: Petheric Press

Limited, 1981), 67.

[3] Hutton, Valley Gold, 67.

[4] Hutton, Valley Gold, 67. The Province of Nova Scotia purchased land for the Experimental Farm in 1910 and the facility was established under Federal Government auspices the following year, with the facility’s large dairy barn and Superintendent’s house being completed in 1912.

[5] Hutton, Valley Gold, 67.

[6] Hutton, Valley Gold, 68.

[7] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 2.

[8] Claire Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm” (Unpublished MS, 2014), 2.

[9] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 2.

[10] Acadia Athenaeum (March 1900), as quoted in Tom Sheppard, Acadia University. Images of Our Past Series. (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing. 2013), 22.

[11] “Treasurer Accounts: Farm”, Acadia Bulletin. November 1912.

[12] Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator (http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/). Accessed June 2015.

[13] Sheppard, Acadia University, 22.

[14] Sheppard, Acadia University, 22.

[15] Sheppard, Acadia University, 23.

[16] Tom Sheppard, Historic Wolfville, Grand Pré and Countryside. Images of Our Past Series (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2003), 95.

[17] Sheppard, Historic Wolfville, 95.

[18] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 3.

[19] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 4.

[20] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 4.

[21] “New Barn” Acadia Bulletin (January 1, 1913), 4-5.

[22] “Treasurer Accounts: Farm”, Acadia Bulletin. November 1914.

[23] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 3.

[24] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 4.

[25] Dutkewych, “The Acadia University Farm”, 4.

[26] Sheppard, Historic Wolfville, 95.

[27] Sheppard, Historic Wolfville, 95.

[28] Donald Oliver, “Farm, Former Part of College Domain Erased From Scene” Acadia Bulletin, (September 1959), 35.

[29] Oliver, “Farm, Former Part of College Domain,” 35.

[30] “Treasurer Accounts: Farm”, Acadia Bulletin. November 1925.

[31] Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator (http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/). Accessed June 2015.

[32] These figures in 2015 dollars amount to an annual deficit in 1928 of $21,221.06 and an accumulated deficit of $135,437.27, as per the Bank of Canada inflation calculator. (http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/). Accessed June 2015.

[33] Sheppard, Acadia University, 22.

[34] Sheppard, Acadia University, 22.

[35] Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator (http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/). Accessed June 2015.

[36] “Treasurer Accounts: Farm”, Acadia Bulletin. (1931).

[37] “Death of Mr. William Oliver” Acadia Bulletin. (June 1934), 21.

[38] Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator (http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/). Accessed June 2015.

[39] “Treasurer Accounts: Farm”, Acadia Bulletin. (1939).

[40] “Valley Farms Are Analyzed” Wolfville Acadian, April 30, 1931.

[41] “Valley Farms Are Analyzed” Wolfville Acadian, April 30, 1931.

[42] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1956, 149.

[43] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1956, 149.

[44] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1955.

[45] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1954.

[46] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1955, 49.

[47] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1955, 49.

[48] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1956, 149. For a detailed discussion of the impact of severe weather on the Annapolis Valley, with particular attention to the impact of Hurrican Edna, see Allan J. MacDonald, “Winds of Change: Severe Weather in the Annapolis Valley,” B.A. Hons. Thesis, Dept. of History and Classics, Acadia University, 2006.

[49] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1956, 149.

[50] Oliver, “Farm, Former Part of College Domain,” 35.

[51] Oliver, “Farm, Former Part of College Domain,” 35.

[52] Oliver, “Farm, Former Part of College Domain,” 35.

[53] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1955, 90.

[54] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report 1955, 91.

[55] Nova Scotia Fruit Growers’ Association Annual Report, 1955, 94.

[56] Oliver, “Farm, Former Part of College Domain,” 35.